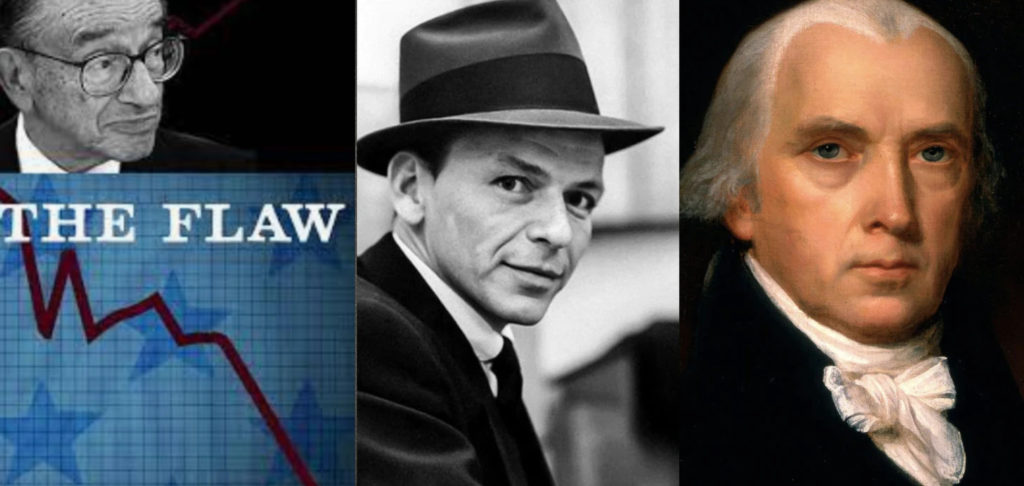

What Do Frank Sinatra, Alan Greenspan, Ayn Rand, and James Madison All Have in Common?

A Hole in the Head was the title of a 1959 film starring Frank Sinatra, in which he introduced the Oscar winning song “High Hopes,” the beginning of which went,

Next time you’re found with your chin on the ground

There’s a lot to be learned, so look around

Just what makes that little old ant

Think he’ll move that rubber tree plant

Anyone knows an ant, can’t

Move a rubber tree plant

Cause he had high hopes, he had high hopes,

He had high apple pie, in the sky hopes…

Sinatra reprised the song for the 1960 presidential campaign of John F. Kennedy, singing

Everyone is voting for Jack

’Cause he’s got what all the rest lack

Everyone wants to back — Jack

Jack is on the right track

’Cause he’s got high hopes

He’s got high hopes

1960 is the year for his high hopes

Sinatra was an ardent Kennedy supporter; and before Kennedy, Sinatra campaigned for Democrats FDR, Harry Truman, and Adlai Stevenson. He was also outspoken against racism—he put on a benefit concert for Martin Luther King Jr. and was instrumental in ending segregation in Las Vegas casinos and hotels—and was concerned about the poor and working class. His outspokenness about social issues led him to be accused of being a Communist.

But perhaps Sinatra had a hole in his head, because by 1972 he did an about face, supporting Republican Richard Nixon, and then campaigning for Ronald Reagan in 1980, when Reagan ran for president. In addition, he no longer was interested or spoke about racial issues.

That term, a hole in the head, formally became known as “The Flaw” in 2008, when Alan Greenspan used the term to describe his own hole in the head.

Greenspan, who from 1987 to 2006 served as the chair of the Federal Reserve, was the man once hailed as an “oracle” and a “maestro” (as the title of a book about Greenspan written by Bob Woodward called him). Yet on October 23, 2008, at the age of 82, he found himself unceremoniously summoned to testify in front of Congress to explain the financial crisis that was beginning to explode across the U.S. and world.

Greenspan wasn’t used to being grilled in the harshest of ways, but to the members of the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform who were channeling their constituent’s anger, they came to play hardball.

“You had the authority to prevent irresponsible lending practices that led to the subprime mortgage crisis. You were advised to do so by many others,” said Representative Henry A. Waxman of California, chairman of the committee. “Do you feel that your ideology pushed you to make decisions that you wish you had not made?”

Greenspan conceded: “Yes, I’ve found a flaw. I don’t know how significant or permanent it is. But I’ve been very distressed by that fact.”

A flaw? Heads exploded.

The exchange between Congressman Waxman and Alan Greenspan continued:

WAXMAN: You found a flaw in the reality—

GREENSPAN: Flaw in the model that I perceived as the critical functioning structure that defines how the world works, so to speak.

WAXMAN: In other words, you found that your view of the world, your ideology was not right. It was not working.

GREENSPAN: Precisely. That’s precisely the reason I was shocked, because I had been going for 40 years or more with very considerable evidence that it was working exceptionally well.

Greenspan clarified further by saying, “I made a mistake in presuming that the self-interests of organizations, specifically banks and others, were such that they were best capable of protecting their own shareholders and their equity in the firms.”

Alan Greenspan found a flaw in his worldview—it was his hole in the head. He realized the operating principle that he lived his life by was flawed.

If Greenspan were Japanese, he would have performed hari kari, the traditional ritualistic act of suicide done by Japanese who had shamed themselves, their families, and/or society. But instead, Greenspan walked away, wrote his memoirs, and got on with his life, while the rest of society paid the price for Greenspan’s flaw—his flaw led to the financial crash of 2008.

His flaw was his pristine belief in the power of the marketplace, that regulations weren’t needed to oversee the marketplace and that corporations and banks would equate their own best interests with the best interests of society. That was a big mistake, and as the banks, financial industry, and mortgage industry played casino with other people’s money, they crashed the world economy.

Greenspan’s flaw was implanted in his head by his longtime mentor, Ayn Rand, to whom he had been devoted since he was in his twenties, when he used to sit at her feet and absorb her ideas.

Rand, the influential author of The Fountainhead and Atlas Shrugged, among other writings, has been a significant influence on libertarians and American conservatives. She called her philosophy “objectivism.” Objectivism’s founding tenet was individualism, as rugged as it could get, above all else.

Objectivism rejected altruism—Rand called altruism “evil”—and supported free-market, laissez-faire capitalism, which she defined as a system based on recognizing individual rights. The Objectivist movement, which Rand’s books inspired, began in the 1950s with a group called “The Collective.” Alan Greenspan was one of the founding members of that group.

The group met with Rand on weekends at her apartment on East 36th Street in New York City to discuss philosophy. Greenspan recalled being drawn to Rand because of a shared belief in “the importance of mathematics and intellectual rigor.” The group met at least once a week, often discussing and debating into the early morning hours. About these discussions Greenspan said, “Talking to Ayn Rand was like starting a game of chess thinking I was good, and suddenly finding myself in checkmate.”

But Rand was a cult leader, a person with a flaw the size of the Grand Canyon. She expelled members of The Collective left and right, ostensibly because they weren’t true to Rand’s teachings; but in reality she expelled them because she despised the fact that they couldn’t get with the program that altruism was evil, selfishness should be the primary force for humans, and people who didn’t have enough money and/or relied on government assistance were losers and parasites.

Rand has influenced many, many people over the years, and all of them have come to be possessed with The Flaw; Rand’s influence has led to a lacking in empathy in her devotees, and a lack of concern for those who never had the same advantages or opportunities.

The best summation of Rand’s influence comes from the screenwriter John Rogers, who said:

“There are two novels that can change a bookish fourteen-year old’s life: The Lord of the Rings and Atlas Shrugged. One is a childish fantasy that often engenders a lifelong obsession with its unbelievable heroes, leading to an emotionally stunted, socially crippled adulthood, unable to deal with the real world. The other, of course, involves orcs.”

But Rand wasn’t the first in the U.S. to have The Flaw. That honor goes to James Madison, fourth president of the U.S. and the person considered the author of the U.S. Constitution.

Madison’s flaw was fueled by his aristocratic upbringing; he came to believe that the country needed to be protected from what he saw as the “tyranny of the majority”—that if the majority had power, they would subvert the rights of the minority.

Who was the majority? The ordinary people, who at that time constituted farmers, the poor, slaves, women, artisans, and tradesmen. Madison was deluding himself with his belief in a tyranny of the majority, because the majority had no say; it was the minority—the elite landowners, bankers, slaveowners, and a few others—who ruled the land.

Madison wrote the U.S. Constitution to protect this minority, and in doing so, created a tyranny of the minority. The majority was looked down on as an unruly, unkempt hot mess; it was the refined elite, through their benevolence and good grace that, by their own self-professed superiority, were saving the majority from doing themselves in.

This was a major flaw on Madison’s part, but because The Flaw would only be discovered in 2008 by Alan Greenspan, suffice it to say that Madison had a hole in the head.

To protect against his belief in a tyranny of the majority, Madison created the representational and republican form of government that the U.S. has, one that grants people the right to elect representatives, but then disenfranchises them to the greatest extent possible.

As two examples of this, until the 17th amendment became law in 1913, the general public wasn’t able to directly elect U.S. senators—and even though senators are now elected directly, the Senate has never been proportionally representative of the population; secondly, with the presidential election, the citizenry doesn’t directly elect the president but instead votes for an electoral college—which, as witness from the elections of 2000 and 2016, the winner of the popular vote total doesn’t necessarily become president.

And it’s Madison’s flaw that has created the sad state of affairs in America now, where both sides of the political spectrum are locked in battles over cultural issues, while missing the bigger picture—the fact that they all are being screwed over by the wealth class.

Madison’s flaw was so deep that he couldn’t take into account his mentor Thomas Jefferson’s political leanings. Jefferson and his good friend Thomas Paine were much more interested in egalitarian rights, but their voices were not heard as Madison wrote the Constitution.

Thanks to Madison’s flaw, the entire underlying structure of the U.S. has The Flaw—the flaw of the tyranny of the minority. And this is what anyone interested in creating a better world is up against—The Flaw.

But just as Frank Sinatra sang, the antidote of The Flaw, the hole in the head, is this: High Hopes—and here’s the full lyrics for you to sing along:

Next time you’re found with your chin on the ground

There’s a lot to be learned, so look around

Just what makes that little old ant

Think he’ll move that rubber tree plant

Anyone knows an ant, can’t

Move a rubber tree plant

But he’s got high hopes, he’s got high hopes

He’s got high apple pie, in the sky hopes

So any time your gettin’ low

’Stead of lettin’ go

Just remember that ant

Oops there goes another rubber tree plant

When troubles call, and your back’s to the wall

There’s a lot to be learned, that wall could fall

Once there was a silly old ram

Thought he’d punch a hole in a dam

No one could make that ram, scram

He kept buttin’ that dam

Cause he had high hopes, he had high hopes

He had high apple pie, in the sky hopes

So any time your feelin’ bad

’stead of feelin’ sad

Just remember that ram

Oops there goes a billion kilowatt dam

All problems just a toy balloon

They’ll be bursted soon

They’re just bound to go pop

Oops there goes another problem kerplop

Leave a Reply